The young run immediately from the eggs like partridges, and are withdrawn to some flinty field by their dam, where they skulk among the stones, which are their best security for their feathers are so exactly the colour of our grey spotted flints.Any evening you may hear them about the village, for they make a clamour that may be heard a mile"(p.52, 1988). White's detailed observations beg reading more than a sentence, as in his letter of April 18, 1768, begining with Stone Curlews, laying two eggs on ground, so "a countryman, stirring his fallows, often destroys them.

GW takes you into another world, the world where quotidian life-the appearance of migratory birds, the Tortoise Timothy in the root garden-was prized, not avoided by iphones and fast transport and vague urgencies.

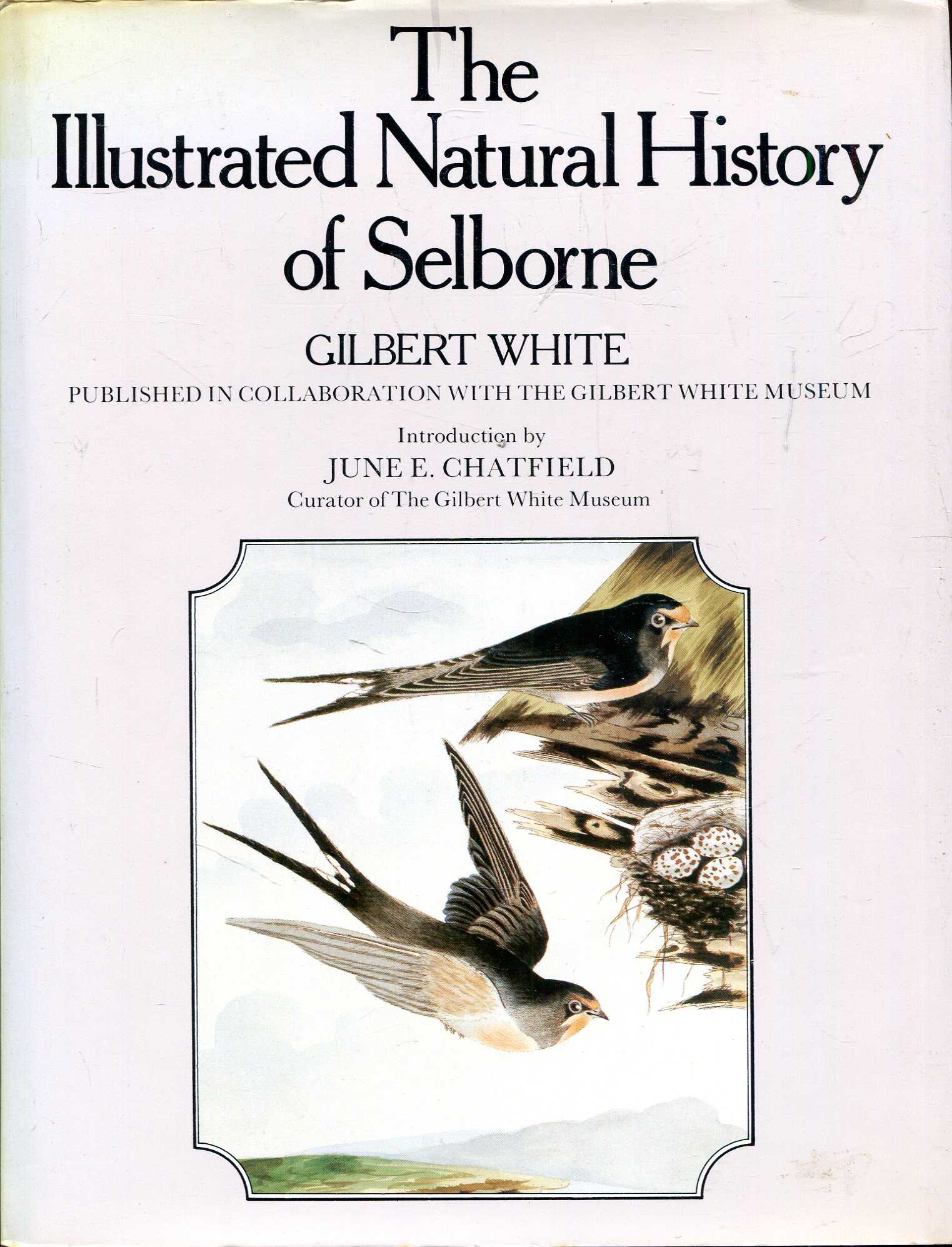

I read White's Selborne, and mused on it so, while traveling in Dorset and writing my Birdtalk (2003). Or one sentence: "The language of birds is very ancient and like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical little is said, but much is meant and understood." Gilbert White's classic, best in an illustrated edition like Century (1988), can be read like the Bible, a few paragraphs a day to muse on.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)